Case Studies

West India Dock Phragmites Bed

Grid Reference TQ3837979813

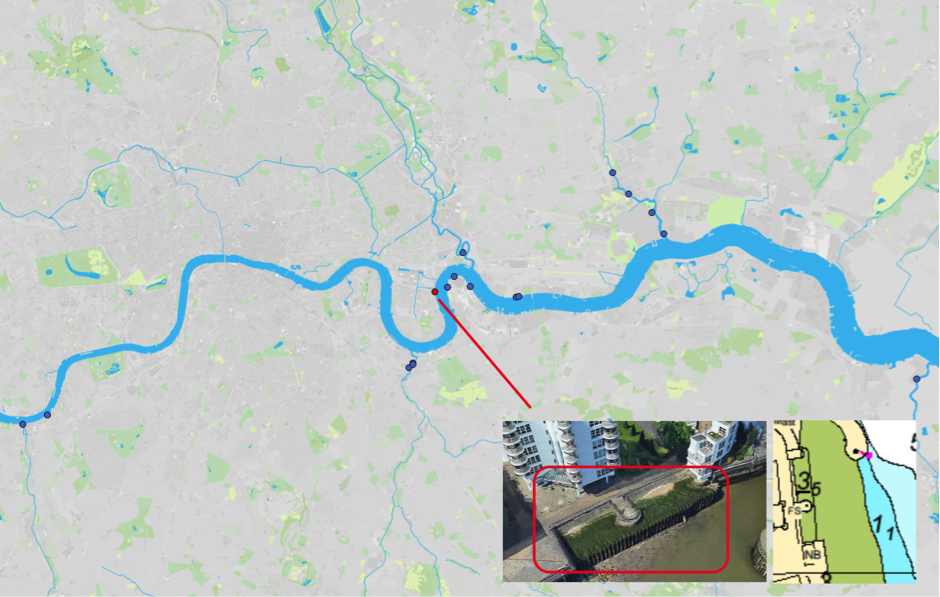

Figure 1: Map of Estuary edges sites pinpointing West India Dock Phragmites Bed; inset graphics include Google Earth aerial photo of site and chart extract of Site (heights in metres relative to Chart Datum).

1. Introduction

1.1 Site Conditions Summary

| Salinity (during low fluvial flows) | ~5.2‰ (Wade, Hawes and Mulder, 2017) |

| Date of construction | 2000 |

| Tidal Range | 6.6m |

| Percentage of area accreted above design level | 97% |

| Degree of exposure to waves: | High |

| Degree of exposure to currents: | Medium |

| Max wave height | PLA? |

| Slope direction | East |

| Slope angle | 1 in 8 normal to flow, near horizontal parallel to flow. |

| Average Whole Structure lifespan | Not measured. |

Table 1: Site conditions summary.

1.2 Site Characteristics

- Here the estuary is about 3‰ salinity and true saltmarsh species should naturally begin to occurring in abundance. Can be referred to as middle estuary.

- Outside of the meander bend and therefore subject to high currents but sheltered to some degree by the timber guiding walls at entrance to West India Dock.

- Sheltered from the prevailing south-south-westerly wind and therefore wind generated waves.

- The location and height of this site away from the channel means that there are limited navigational concerns.

- The estuary is wide here and therefore wave reflection will be less than the upper estuary locations.

- Adjacent to a permissive/extended section of the Thames Path and a built-up residential area, visibility from occasional passers-by and residential flats.

1.3. What the developers did

- Installed a new fronting sheet steel pile wall truncated not far below mean high water spring tide level to enable only occasional inundation of a new terrace.

- Created a sloping terrace behind this sheet steep piles at an angle of approximately 1 in 8 and backed this with stone paving at an angle of about 45o sloping up to the backing flood wall (construction unknown).

- Installed a new section of Thames path overlooking the terrace and a private seating area with a locked gate on a raised peninsula dissecting the terrace.

- Pre-planting was conducted with common phragmites. Contractors now manage these but cutting them back in the winter months.

2. Aerial photo and as-built drawings: plan view and cross-sectional view

Figure 2: Aerial view of site (Google 3D image from 2018)

(a)(b)

(c)

Figure 3: Selection of photos from Winter/Spring 2017 to give an idea for the construction and setting: (a) Sheet steel pile and terrace, (b) Sloping stone paving at rear of terrace and (c) timber guiding walls to the south of the entrance to West India Dock. Source: Jacobs (TEAM 2100).

3. Environmental

3.1 Inundation

The immediate area of river in front of the terrace is significantly lower than the terrace, the foreshore dries during low tides and is predominantly silty foreshore with some gravel.

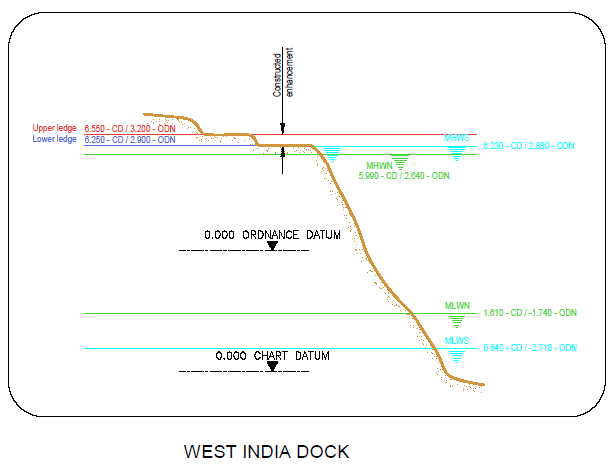

During larger tides (spring) the terrace has water on it for over six hours 25 minutes while the top of the terrace is covered for almost two hours. During smaller (neap) tides the terrace has water on it for 25minutes and the top of the terrace is only reached for 10 minutes.

Figure 6: cross section of elevation of constructions (heights in CD)

3.2 Biodiversity

Adjacent Site:

Point Wharf is directly opposite. Wave, current and light availability may be different but otherwise it is similarly located in the open estuary.

Fish:

Only one fish, a European eel (Anguila anguila) was captured in the 2017 survey at this site. However, fish assemblages should resemble those found at the adjacent site. The height of the terrace will dissuade benthic species such as flounder and gobies from accessing the site, since these appear to follow gradient and do not like “steps” (Colclough, et al, 2004). There is no reason why pelagic species such as bass or dace would not use this site. Reasoning for the low levels of recording on the dock itself could include:

- The height of the terrace, which dissuades fish from accessing the dock

- The “steps” (Colclough, et al, 2004) of the dock make it more difficult to access, as opposed to other sites which have gradients

Botany:

This site was diverse but struggling to thrive. Common reed (Phragmites australis) (Figure 7) was found to have stunted, sparse growth. The rear and uppermost section of the terrace was largely made up of shingle and the concrete slab river wall was partially scoured, indicating a relatively high energy aquatic environment which, usually, is not common reed’s preferred habitat. Saline and estuarine plants were found along the site. These included: Sea Aster (Aster tripolium), English Scurvygrass (Cochlearia anglica), Sea Beet (Beta vulgaris subsp. maritima), and colonies of stone and wood algae, particularly Gutweed (Ulva linza). For details of all species recorded, please see the botany report 2017. Links in the Further Reading section.

Figure 7: West India Dock Reedbed. Left to right: Flowering plant of common reed. Eastern section of reedbed with gravel and river wall scouring visible on the left. Also, note the relatively sparse and largely non-flowering growth of the common reed compared to the plants in figure 9.

Figure 8: West India Dock Reedbed. Left to right: Non-flowering rosettes of English scurvygrass. Mature fruiting and flowering plants of sea aster. This is the ‘radiate’ form of the species (bearing light purple ‘petals’), in most SE England saltmarsh habitats the form without rays is apparently more frequent than this form.

Figure 9: West India Dock Reedbed. Left: Brickwork and wood being colonised by algae. Right: Gutweed forming extensive patches in the gaps between the stems of common reed.

| Planted | Natural Colonised | Dominant | Notable species |

| Common reed (Phragmites australis) | Sea Aster (Aster tripolium) | ||

| English Scurvygrass (Cochlearia anglica) | |||

| Sea Beet (Beta vulgaris subsp. maritima) | |||

| Gutweed (Ulva linza) |

Table 2: Showing the planted, assumed naturally colonised, dominant and notable species found at the site. For full details of all species recorded, see the botany report 2017.

Invertebrates:

The habitat is Littoral sandy mud (LS.LMu.MEst.HedMac) and well-sorted gravel or coarse sand (LS.LCS.Sh.Pec). The invertebrate assemblage present suggests that the succession of this habitat has progressed independently to two difference habitat types (Figure 8) both of which are at the 5th level of 6 possible on the Joint Nature Conservation Committee classification system. This suggests this habitat is performing well.

Figure 8: 2 possible Joint Nature Conservation Committee classification system codes for the habitat based on the invertebrate assemblage.

3.3 Geomorphology

97% of the accretable area has accreted with sediment above the design level (Figure 8).

Figure 9: Schematic showing geomorphology and basic ecology.

Contributing reasons for this include:

- Sheltered from the prevailing south-south-westerly wind;

- Well recessed behind northern and southern river walls protecting from currents found on the outside of the meander bend.

- West India dock timber guiding wall protecting from some currents and vessel generated waves.

- Preplanted with mature phragmites which absorbs some wave energy.

- Shallow gradient.

- Vessel generated waves have been seen to run along the north facing (opposing the vessel direction) walls, scouring out fill (3%) (Figure 10) and depositing it at the back of the terrace in 2 places (Figure 11)

Figure 10: West India Dock Phragmites Beds: Scoured out sediment at southern most end, Autumn 2017, 17 years since construction. Source: Steve Colclough.

Figure 11: West India Dock Phragmites Beds: Scoured out sediment at southern most end, Winter/Spring 2017, 17 years since construction. Source: Environment Agency.

4. Social, Litter, Safety and Navigation

4.1 Social

The site is not publicly accessible and therefore no social surveys were completed as part of this review. There is a large residential presence, however, and surveys should be conducted with those living in the blocks overlooking the terrace.

4.2 Litter

West India Dock Phragmites beds gathers little litter (Figure 12). It is well managed and much of this may therefore could be removed through maintenance.

Figure 12: Limited litter collected at West India Dock Phragmites Beds, October 2017. Scour: Steve Coclough.

4.3 Safety and Navigation

The location and height of this site away from the channel means that there are limited navigational concerns. However safety for access and exit is more concerning with the drop from the lower terrace to the foreshore and limited ladders and chains in the area.

5. Engineering

No official engineering assessment was conducted at this site. However, the geomorphological assessment does indicate that the north facing walls would benefit from fewer sharp interfaces and from the placement of rock armour to prevent scour from vessel generated waves.

6. Conclusions

6.1 Within the first 18 Years since Construction (2000 to 2018)

(This site was not included in the 2008 Estuary Edges document):

- The good accretion of sediment on this terrace combined with the luxuriant, diverse vegetation growth and great habitat progression as shown by the invertebrate assemblage makes this site a reasonable success.

- The site’s biggest problem is that it has sharp fronting edges which dissuade bottom dwelling fish such as flounder from accessing the site. The guidelines specific to intertidal vegetated terraces and for fish both stress this point. These edges are also very high, close to mean high water spring tide level, meaning that inundation is infrequent and short-lived. This explains the finding of only one fish (an eel).

- The north facing (opposing the vessel direction) walls would benefit from fewer sharp interfaces and from the placement of rock armour to prevent scour from vessel generated waves. This is stressed in the Geomorphology

- The site performs well for litter (although this may be partly management) and for safety and navigation.